You might have noticed that I put up a little section on the site about a D&D add-on called Wild Magic that I thought up this last year. Right now there’s only a conceptual description of what the add-on tries to achieve, what motifs it explores and where I stole them. In reality, the system is a little further along, with only a few gaps left to fill before I can reasonably put it online for you to have a look.

Since it’s my system, I was able to cover said gaps with improvisation and start playtesting it with both my current D&D groups* back in October. We’re not too far along in either campaign, but starting to get a feel for it. My plan is to write extensively about all the rulemaking and balancing on here, maybe get a dialog going with you as I refine the system. However, that’ll only really make sense once a first version of the rulebook is available as a basis of discussion. In this article, I want to talk about something… well, not something completely different, but only loosely related at best.

So, here’s the deal; both aforementioned campaigns take place in the same world, albeit in different countries. The world still lacks a name, but it has an ample supply of three moons. The reason for the latter – besides me wanting to be original and inventive only to discover that there’s already tons of worlds with three moons – is that in Wild Magic, there are these magical circumstances that mess with your spellcasting and change daily and are determined using three tarot cards.** And the system doesn’t give a good reason as to why it’s three cards. It just seemed right at the time. So I wanted to put some lore behind the mechanics, have three moons and have those moons be gods whose moods influence magic, the whole shebang.

It seemed simple enough at first; I just had to come up with cool names for my moons, and maybe some idea of their optics and size and order. When you lay out the tarot cards to determine the magical circumstances, you always turn over and ignore one of them based on which season it is in your game. More specifically, there’s a card for summer / fall, one for winter / spring, and one that’s permanent. I used that for my moons, naming the closest “Die Warme Schwester”, which is german for “The Warm Sister”. It’s huge and orange and I imagine it makes for some great scenery in the summer. During winter, its light fades and it’s just a big grey-white ball. That is when “Harte Zeiten” (“Hard Times”), little more than a tiny blue-black rock, becomes better visible and takes over until it fades out again in late spring. Unimpressed by their back and forth, the medium-sized brown and icy “Treumond” (“Trusty Moon”) is the farthest out, yet always visible. I noted down that there would be an ancient religion based around them, the “Dreimondkirche”. Which literally translates to “church of the three moons”. Not my most exciting invention, but entirely sufficient as long as noone would play a cleric and choose to be a part of it. Boom. Done.

Well, noone did build a cleric of the three moons. But one of my more experienced players – let’s call him Salazar, as that’s his character’s name – asked me if he could be a lycanthrope. And thus my journey began.

First off, he and I homebrewed some mechanics for a player character weretiger, since the Monster Manual only has a few rough notes on that, which, simply added on top of a regular build, sounded a little overpowered to both of us. We essentially made it a background, granting him specific transformative powers but also imposing some weaknesses, including – naturally – the possibility of involuntary transformations in case of a full moon.*** Still, it was pretty powerful for a background, so we gave him only the most basic of possessions. Five gold pieces, a set of common clothes studded with a suspicious amount of large stitches, and – I didn’t want him to be completely screwed in this moon-rich environment, and honestly, if I were a lycanthrope, it would be the first thing I’d get – “a piece of parchment depicting the phases of the lunar system”. In other words, a moon calendar.

Now, could I simply have gone ahead and played the game and inserted a full moon every now and then, maybe even used them as a plot device? Yes. Very much so. But then I would have had to worry about over- or underusing them. And didn’t Gygax himself (in another time and context) write that tracking time is necessary to achieve any sort of relevance in RPGs? Something like that? I’m not sure I agree, but it can’t hurt to try it. And anyways, I’m not merely a D&D-crazed lunatic (get it?) overpreparing for the first session of his first homebrew campaign – I’m a programmer! I cannot besmirch my honor manually managing lunar cycles!

And how hard can it be? You just pick which moon takes how long to circle your planet and map the results out over the year. Of course, to be able to reuse that calendar for the following year, your orbit periods have to be a factor of the number of days in a year to avoid shifts. And leap years can’t be a thing. All acceptable, but do I even want that? Do I want poor Salazar to count his days on a giant boring calendar? I do not. That’s all overhead and no fun. I want him hunched over a mystical device, tracing the fate of the universe with his fingertips! And I want him to do it on A4 paper.

So if I want a reusable calendar anyway, why track the whole year in the first place? All I really need to map out are the days it takes for the whole moonglomerate to come full circle. The lowest common multiple of orbit periods.**** Say for example The Warm Sister (TWS) circles at 16 days, Hard Times (HT) at 42 days and Trusty Moon (TM) at 57, as divinely decreed by Our Lady of Whole Numbers and Calculatory Ease. In that case, it would take 24 * 3 * 7 * 19 = 6384 days for the pattern of constellations to repeat itself. Which, admittedly, is a bit more than a year. But there’s a simple way to tame these numbers, the same as before; make the shorter orbit periods factors of the longest one. This time without worrying about implications on leap years or anything.

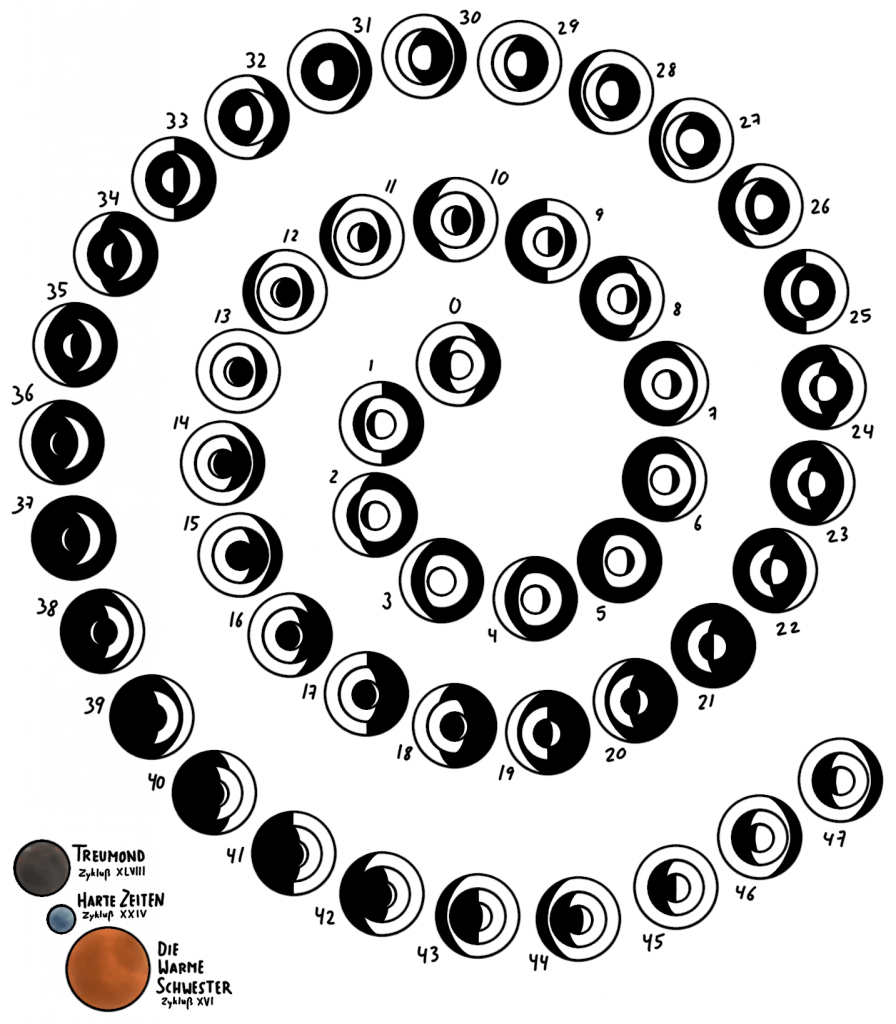

Following this thought, I played around a little. I wanted to draw as few moons as possible but I didn’t want a full moon every second day either. After careful consideration, I ended up choosing orbit periods of 48 for TM, 24 (half TM) for HT, and 16 (a third of TM) for TWS. Lowest common multiple: 48. Way better. Since the two shorter periods are not factors of each other, the whole thing yields an interesting enough pattern that doesn’t seem overly artificial. This is furthered by the offsets, which I chose to be +7, +3 and +13. I figured prime numbers were an easy – if overkill – way to avoid accidental full moon overlaps. I might introduce a double or triple full moon as a plot-relevant cosmic event at some point but I don’t want one every 48 days. So I went with six singular full moons per 48 days. That’s a full moon every eighth day on average. Not exactly lycanthrope-friendly but not an endless howlfest either.

So far, so good. Though, you know, 48 * 3 is still a lot of moons to draw and fit on that A4 sheet. After considering and discarding layout ideas including three concentric circles (too spacious), a table structure (too boring), and some weird cheese-slice design (too impractical), I arrived at a spiral type thing. Circle-adjacent and thus reasonably easy to navigate, yet a lot more compact. To get a decent spiral and save even more space, I placed the moons inside of each other by size. I shackled myself to my Wacom for two nights and this is what I got:

I named it “Luddsteins Kalendarium”, “Kalendarium” being an old german word for calendar from the middle ages. It comes from the Latin “Calendarium”, which I think reads smoother in English. Luddstein is probably some long-dead halfling academic and / or inventor in my nameless world.

Whoever he was, I’m fairly satisfied with his work. I want (my players) to have artifacts that are compact and easy to use but make you look and feel smart and awesome and mystical when you do. I feel like Luddstein’s Calendarium achieves that quite well.

There are however some cosmetic aspects I’d change if I were to make another. First, I wouldn’t use the same fill and border color for the moon circles. I figure that would make the full moons easier to identify. Unfortunately, I kind of messed up my layer management, so correcting that would mean work. Second, I’d start the index at one, not zero. Classic programmer’s habit, not useful here at all.

What do you think?

(Loosely) related material:

- I was very focused on creating an artifact here, and willing to oversimplify things. If you want a more accurate single- or multi-moon system and don’t need to have it on one page, try Fantasy Calendar or a similar site (there’s plenty). You can name your months and weekdays with it and invent holidays and stuff. There are also some classic fantasy calendars available as presets.

- There’s a fairly comprehensive video by Matthew Colville about the aforementioned Gygax quote, tracking time in modern D&D campaigns, and how crafting a calendar for your campaign can impact your worldbuilding.

- If you’re specifically looking to cultivate your homebrew calendar with meaningful holidays, check out this video by Dael Kingsmill for a wagonload of conceptual knowledge.

* The first is a table of four friends that I meet mainly for D&D. Three of them showed me the ropes in my very first game about one and a half years back. They’re rather experienced and used to my bullshit. The second group consists of five of my coworkers. I got them into the game in January, all newbies, and we’ve played sporadically since then. They’re still learning. The fact that they’re mainly learning from me worries me sometimes. Maybe I should have stuck to the base rules with them? We’ll see. They’re smart people.

** I want to assure you that it’s not as complicated as it sounds, but my gut tells me I would be lying. Also, it’s actually eight tarot cards in total, but only the central three are important for this piece.

*** Another weakness was vulnerability to silvered weapons, with an especially nasty rule for damage from ingested silver. Wild Magic has rules for alchemy and many of the potions are made with powdered silver, an ingredient that also features a lot in the Player’s Handbook, e.g. as a component for crafting holy water. All in all I was fairly proud of our build. I could share it if you’re interested.

**** One of my best friends, a recovering astrophysicist, tells me that a multi-moon system like this is actually very unlikely to be stable. As far as I understand, which is not very far at all, the orbit periods would not be fixed numbers in reality. But fixing things is what magic is for.